It’s one of the most common, and contagious, human behaviors.

You could be sitting in a meeting, watching a late-night movie, or even reading this article right now when it happens: your mouth stretches wide, your lungs pull in a deep breath, your eyes water slightly, and you release a long sigh. You’ve just yawned.

Yawning feels so ordinary that most of us never question it, yet it remains one of biology’s most puzzling reflexes. People and animals alike do it, from humans to dogs, birds, and even fish, but scientists are still unraveling why we yawn often and what purpose it truly serves.

In this deep-dive exploration, we’ll unpack what modern research says about yawning: what triggers it, what myths persist (like the old oxygen theory), and what clues it offers about our brains, bodies, and emotions. We’ll also explore when frequent yawning might indicate something more than tiredness and deserves a closer look.

What Exactly Is a Yawn?

A yawn is a complex physiological response that combines movement, breathing, and brain function. It usually involves:

-

A deep inhalation through the mouth.

-

Stretching of facial and jaw muscles.

-

A brief pause as air fills the lungs.

-

A slow exhalation, sometimes followed by a sigh.

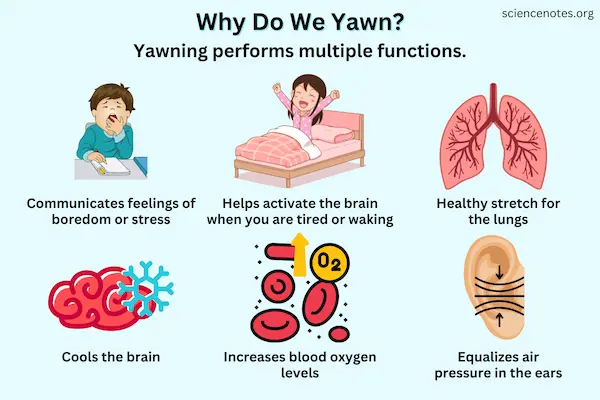

Although simple in appearance, yawning engages multiple body systems — the nervous system, respiratory system, and circulatory system — all working together in a single, coordinated act that scientists believe has multiple overlapping functions.

How Common Is Yawning?

It’s universal. Every human does it, often without realizing how frequently. On average, most adults yawn between 5 and 10 times per day, though the number can vary depending on sleep quality, temperature, stress, and even social environment.

Interestingly, yawning begins long before birth — ultrasounds show fetuses yawning in the womb, suggesting it’s an instinctive reflex deeply embedded in our biology.

The Classic Explanation: The Oxygen Myth

For decades, textbooks repeated the idea that yawning helps us get more oxygen or remove carbon dioxide from the bloodstream. The logic seemed straightforward: when we’re tired or bored, we breathe more slowly, so a yawn supposedly “resets” oxygen levels.

However, scientific tests have disproved this theory. Experiments in which participants breathed air with varying oxygen and carbon dioxide levels found no significant change in yawning frequency. In other words, yawning isn’t about air — it’s about the brain.

The Cooling Theory: A Chill for the Brain

One of the most widely accepted modern explanations is the brain cooling theory. According to this idea, yawning helps regulate brain temperature, keeping it within the optimal range for alertness and performance.

Here’s how it works step by step:

-

The Yawn Begins: You take a deep breath, pulling cool air into your mouth and nasal passages.

-

Increased Blood Flow: The movement stretches muscles and boosts circulation to the brain.

-

Heat Exchange: Cool air and enhanced blood flow help dissipate heat, lowering brain temperature slightly.

-

Restored Alertness: A cooler brain functions more efficiently, improving focus and attention.

Researchers have found that yawning tends to occur when the brain might be warming up — for example, during transitions between alertness and sleep or when switching between mental tasks.

Supporting Evidence

-

People yawn more often in warm environments than in cool ones.

-

Applying a cold compress to the forehead reduces yawning frequency.

-

After yawning, people often report feeling slightly more awake or refreshed.

Yawning, then, may act as a kind of natural air conditioner for the mind.

The Transition Theory: Resetting the Brain’s State

Yawning also seems to occur at transitional moments — right before waking up, when getting sleepy, or during moments of boredom. These times have one thing in common: changes in arousal or vigilance.

How This Theory Works

The brain continuously adjusts its alertness level. When we shift between states — from high focus to relaxation, from wakefulness to sleepiness — yawning may serve as a “reset button,” helping the nervous system stabilize and maintain balance.

It’s like the body’s subtle signal that says, “We’re switching gears.”

-

Before sleep: Yawning helps prepare the body for rest.

-

Upon waking: It stimulates muscles and circulation for alertness.

-

During boredom: It re-engages attention when the mind drifts.

In short, yawning might help us stay mentally aligned with what our body is about to do next.

The Social and Contagious Side of Yawning

One of yawning’s strangest features is how easily it spreads. Seeing, hearing, or even reading about yawning can make you do it too — a phenomenon known as contagious yawning.

Why It Happens

Contagious yawning appears linked to empathy and social bonding. Studies show that people are more likely to “catch” a yawn from someone they know — a friend, family member, or colleague — than from a stranger.

Scientists believe this mirrors how social animals synchronize behavior. Among wolves, chimpanzees, and even parrots, contagious yawning seems to help groups stay coordinated — resting, hunting, or waking at the same time.

For humans, it may serve a similar purpose: strengthening unconscious connection through shared physiological signals.

The Neurological Connection: Yawning and the Brain

Yawning involves multiple brain regions, including those that regulate temperature, emotion, and arousal.

Key Areas Involved

-

Hypothalamus: Controls body temperature and sleep cycles.

-

Brainstem: Coordinates breathing and reflex movements.

-

Amygdala: Connects yawning to emotional responses like stress or empathy.

-

Prefrontal Cortex: Helps regulate social behavior and awareness.

This overlap may explain why yawning appears in both physical and emotional contexts — from fatigue to anxiety to empathy.

When Yawning Is a Sign of Something Else

Yawning is usually harmless, but excessive yawning can sometimes point to an underlying issue.

Possible Causes of Frequent Yawning

-

Sleep Deprivation: The most common cause — when the brain craves rest, it triggers yawns to stay alert.

-

Fatigue or Boredom: Low stimulation or mental drift often brings on yawns.

-

Anxiety or Stress: High adrenaline levels can confuse the body’s regulation system, leading to frequent yawning.

-

Medications: Certain antidepressants or antihistamines can increase yawning as a side effect.

-

Heart or Neurological Conditions: In rare cases, excessive yawning may appear with problems affecting the vagus nerve or brainstem.

If yawning happens excessively — especially with dizziness, chest discomfort, or fatigue — it’s worth discussing with a healthcare professional.

Yawning Across the Animal Kingdom

Humans aren’t alone in this curious reflex. Yawning occurs in nearly every vertebrate species studied.

Examples

-

Dogs: Yawn to reduce stress or signal friendliness.

-

Birds: Yawn when adjusting body temperature or preparing to sleep.

-

Fish: Perform similar mouth-stretching motions, possibly for oxygen flow or signaling.

-

Chimpanzees: Display contagious yawning, reflecting complex social awareness similar to humans.

This widespread behavior suggests yawning has deep evolutionary roots — serving functions that may vary by species but share a core purpose of maintaining balance and readiness.

The Link Between Yawning and Sleep

Yawning often marks the border between wakefulness and sleep. It may act as both a physiological and psychological signal that it’s time to rest.

-

Evening Yawns: Help slow breathing and heart rate, promoting relaxation.

-

Morning Yawns: Stretch facial muscles and improve blood circulation, helping the body prepare for movement.

Sleep researchers believe yawning could also synchronize the brain’s internal clocks, helping regulate circadian rhythms — our natural day-night cycles.

The Yawning-Stress Connection

Though commonly associated with tiredness, yawning can also appear during stressful or tense situations — before public speaking, sports competitions, or exams.

This may sound counterintuitive, but stress yawning actually supports the body’s balance. It may:

-

Cool an overheated brain caused by stress.

-

Reset the nervous system’s alertness.

-

Reduce physiological tension before action.

Athletes and soldiers sometimes report yawning right before intense focus moments — a sign their bodies are stabilizing under pressure.

Common Myths About Yawning

1. Myth: Yawning means you’re bored.

Fact: It can also indicate transitions, brain cooling, or even stress regulation — not just boredom.

2. Myth: Only humans yawn.

Fact: Dozens of animal species yawn, suggesting it’s a deeply rooted biological reflex.

3. Myth: You can “catch” a yawn only visually.

Fact: Hearing yawns or even thinking about them can trigger the response.

4. Myth: Yawning fills your body with oxygen.

Fact: Studies show no correlation between yawning and oxygen or carbon dioxide levels.

Understanding what yawning is not helps narrow down what it might truly be — a complex interplay of physiology, psychology, and social behavior.

How to Manage Excessive Yawning

Most yawning needs no treatment, but if it becomes disruptive, you can try simple adjustments to reduce it.

Practical Tips

-

Improve Sleep Quality: Aim for consistent sleep schedules and restful environments.

-

Stay Hydrated: Dehydration can increase fatigue and yawning frequency.

-

Engage in Movement: Gentle stretching or walking can re-energize the body.

-

Manage Stress: Breathing techniques and mindfulness can balance your nervous system.

-

Review Medications: If yawning appears after starting a new prescription, discuss it with your doctor.

These small lifestyle tweaks can often bring yawning back to its normal, healthy rhythm.

Fun and Curious Facts About Yawning

-

Yawning typically lasts between 4 and 7 seconds.

-

You’re more likely to yawn when you’re trying not to.

-

Reading about yawning can make you yawn — a sign of empathy and brain mirroring at work.

-

The average yawn volume fills your lungs with roughly two-thirds more air than a normal breath.

-

Newborns begin yawning around 11 weeks of gestation — before they even breathe air.

Quick Glossary

-

Yawning: A reflex involving deep inhalation, mouth opening, and slow exhalation.

-

Contagious Yawning: The tendency to yawn after seeing or hearing another person yawn.

-

Brain Cooling Theory: The hypothesis that yawning helps regulate brain temperature.

-

Arousal Transition: Shifts in the brain’s alertness level that often trigger yawns.

-

Neural Synchrony: The alignment of brain activity, possibly promoted through contagious yawning.

Summary: What We Know — and Don’t Know — About Yawning

What Science Agrees On

-

Yawning is a universal reflex across many species.

-

It involves temperature regulation, arousal transitions, and social bonding.

-

The oxygen theory has been largely debunked.

-

Excessive yawning can reflect fatigue, stress, or underlying medical issues.

What Remains a Mystery

-

Why yawning is so contagious.

-

Why some people yawn more than others.

-

Whether different types of yawns serve different functions.

Despite centuries of observation, yawning continues to fascinate researchers because it bridges physical, emotional, and social science — a reminder that even the simplest gestures hide deep complexity.

Final Reflection: The Ordinary Mystery of a Yawn

So the next time you yawn, remember — it’s not just your body’s sign of fatigue. It’s a subtle symphony of breath, muscle, and brain activity; a cooling fan for your mind; a quiet social signal; and a relic of evolution that connects us to every creature that ever breathed.

Whether you yawn from tiredness, empathy, or simple curiosity, it’s proof that your body and brain are in constant dialogue — adjusting, balancing, and staying in tune with the world around you.